Folkways in Wonderland (FiW) is a cyberworld for musical discovery with social interaction, allowing avatar-represented users to explore selections from the Smithsonian Folkways world music collection while communicating through text and audio channels. FiW is built on Open Wonderland, a framework for creating collaborative 3D virtual worlds similar to Second Life.

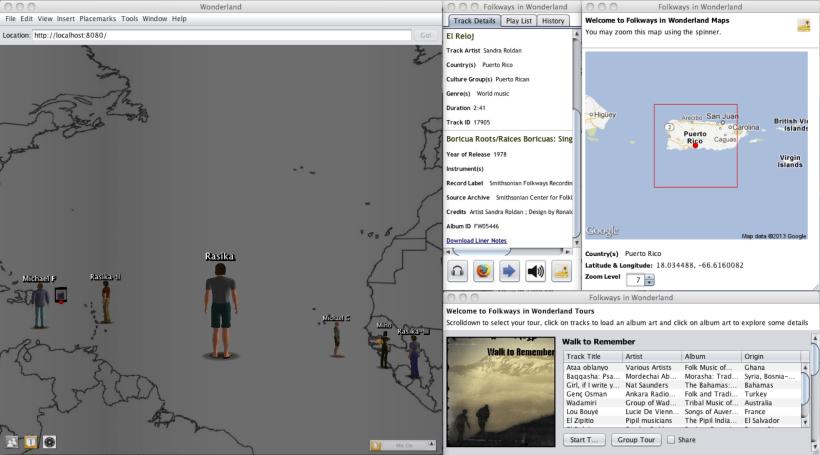

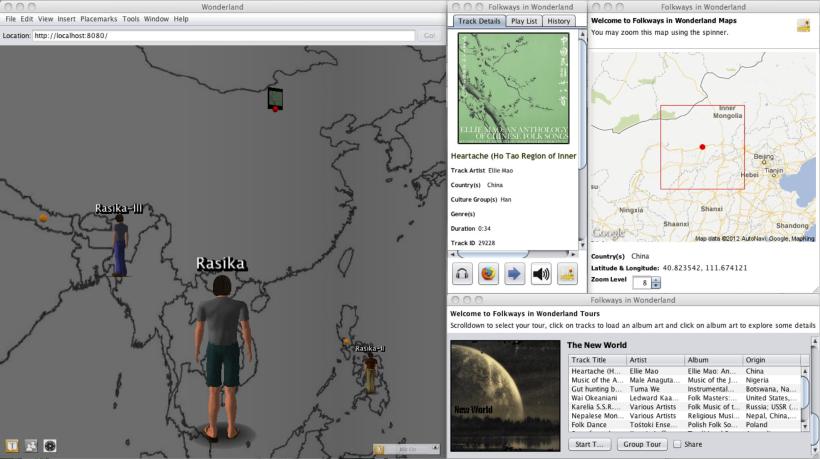

Figure 1. [Click images to enlarge.] A typical Folkways in Wonderland session: In the upper-center window, the user browses metadata for the track (located in Puerto Rico) selected in the left window; buttons allow the user to view liner notes, listen via virtual headphones (excluding competing sounds), locate the track on the Smithsonian Folkways website, teleport to the track’s origin, search for other tracks, or view track location on a zoomable Google map (upper right). The user may also embark on a tour, using a window such as that shown in the lower right.

Our musical cyberworld is called Folkways in Wonderland because it is populated with track samples from Folkways Recordings. Since acquiring the label in 1987, Smithsonian Folkways has expanded and digitized the Folkways collection while enhancing and organizing its metadata, all of which is now available electronically. The Folkways collection thus offers a number of compelling features: it is large, diverse, global, well-documented, and digital. Furthermore, it is, in itself, one of the most important and enduring products of ethnomusicological research ever assembled. From the full Folkways collection, we have selected, encoded, and geotagged a set of 1,166 music tracks, chosen for aesthetic and cultural interest and geographical distribution, to represent a broad spectrum of world music. Out of these, we have selected a smaller number to be embedded in FiW.

Exploring Folkways in Wonderland

Our cyberworld music browser centers upon a cylinder upon which a rectangular map of the world is texture-mapped. Musical tracks are geotagged (according to location of performance, performers, and style), and visually identified by a placemark, a clickable sphere acting as a landmark. Once clicked, a track’s album cover appears above the chosen node, a metadata window (displaying title, artist, album, genre, origin, instruments, and other track-related information) is updated, and a menu item (similar to a bookmark in web browser) is added to the placemarks list in the client browser. The placemark is also a sound source, a virtual stereo speaker display that loops the corresponding audio track, radiating throughout its nimbus and enabling location-aware multisensory browsing.

Multiple avatars can enter the space, listen to these virtual speakers, and contribute their own sounds (typically speech, but potentially music) to the mix. Avatars hear all sound sources (tracks, as well as channels associated with other avatars) within the space, attenuated for distance, and rendered with a spatial sound engine that emulates real-world binaural hearing.

Avatars are free to explore the cyberworld, using keyboard and mouse controls to navigate throughout the cylinder and in the surrounding virtual environment (including a building and a verdant park, suitable for casual conversation or more formal conferencing), while interacting with each other and listening to music. Wonderland supports multiple perspectives, including endocentric (1st-person) and egocentric (2nd-person) points of view.

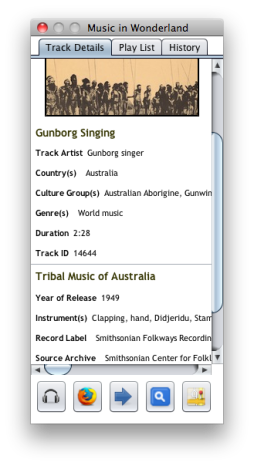

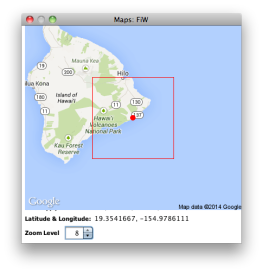

While inside the cylinder, a user may click a marker to highlight a particular track. (For each avatar, only one track may be highlighted at a time.) The corresponding marker changes color from orange to red to indicate its highlighted status; the track’s album cover appears above the marker, and its metadata is displayed in a separate window (as shown in Figure 1 top center and Figure 2), together with a Google map providing detailed, zoomable, topographic information. Buttons are available allowing an avatar to teleport to the selected track’s location, to don virtual headphones connected to this track (thereby excluding competing sounds), to search for other tracks by metadata (users may teleport to a search result by clicking), or to purchase a track. Liner notes may be downloaded as a PDF file (viewable in a separate application).

Avatars can also join any of several configurable tours, organized according to themes (for instance, a tour might feature fiddling around the world), each of which automatically leads them through a sequence of tracks in a predefined order. While visiting a particular track its metadata is displayed; the visiting period is user configurable, and users can also elect to leave a tour at any time. In addition, two track lists can always be displayed: a playlist containing the complete track collection, and a track history listing tracks that have been visited in the current session. A simple text search function is provided to search across all metadata, generating a list of matches. Items appearing on any track list may be clicked to teleport directly to the selected track.

FiW is collaborative: multiple avatars can enter the space, audition track samples, contribute their own sounds (speech or other) to the soundscape, and also communicate through text chat. Nearby users can hear music together, as well as hear and see each other. Wonderland also provides in-world collaborative applications, such as a shared web browser or whiteboard. Thus users are provided with a real-time, immersive, audiovisual representation of the virtual sociomusical environment, together with multiple means of communicating within it.

When tracks and avatars are near each other, overlapping nimbus projections create a dense mix, continuously shifting as the avatar moves and turns, guiding exploration. However, in order to listen to a particular track, an auditory focus function is available, causing other audio streams to be blocked; this narrowcasting feature is described in the next section.

Figure 5. Exterior view of the cyberworld. Figure 5. Exterior view of the cyberworld. |

Figure 6. A discussion park allows quiet conversations among avatars. Figure 6. A discussion park allows quiet conversations among avatars. |

Narrowcasting and Multipresence in Wonderland

While exploring the collaborative musical space, users hear a rich binaural audio mix, spatialized to source locations, whenever those sources (whether tracks or avatars) are nearby. Sometimes users may want to focus auditory attention on a particular source, or conversely may want to address only particular target avatars. Narrowcasting denotes a set of techniques allowing audio streams to be filtered for focus, comprehension, privacy, security, and user interface optimization in groupware applications.

Narrowcasting includes four tools, comprising two complementary pairs: select & mute (applied to sound “sources”, whether tracks or avatars), and attend & deafen (applied to sound “sinks,” or avatars). The “select” (or “solo”) function reduces a soundscape by selecting which sources are audible in the mix; the converse is “mute”, which silences them. The user can likewise limit which avatars will hear his or her own sounds, using “attend” (causing only selected avatars to hear) or “deafen” (the converse). All of these tools can be used to avoid unwanted cacophony, to maintain privacy, or to enable more intimate conversations.

Multipresence allows each user in the virtual environment to create and control multiple avatars (as shown in Figure 7). In this way, a user can interact at more than one position within the virtual environment. For instance, one may wish to accompany different social groups, as they explore and discuss tracks in different parts of the world, or to participate in a virtual conference while listening to a particular track, or to compare two tracks that are distant from one another without having to navigate between them, or to be guided passively through a tour while actively conversing about it. In all these cases, he or she can “fork” presence and locate self-representations at multiple locations of interest. Each such avatar “clone” captures a different soundscape, modifiable by independent narrowcasting options.

Representations of Narrowcasting Operations

Table 1. Various methods for representation of narrowcasting operations.

Table 1. Various methods for representation of narrowcasting operations.

Figure 7. A user with multiple instances of self can audition music in different places at once. The metadata window (top center) shows details of the current musical track with respect to the selected clone. Narrowcasting functions can be used to control soundscapes and filter audio, musical, and textual streams.

Experimenting in FiW: A virtual laboratory for ethnomusicology

We use FiW as a virtual ethnomusicological laboratory for controlled experimentation on the social impact of musical communications in cyberspace. We pose the following general questions: How do social actors, as represented by avatars, interact in an immersive cyberworld when presented with a specific collaborative task (for instance, to locate an audio sample)? What sorts of social groups and interactions emerge through virtual world music interactions, and how do these depend on the kinds of music and actors populating the cyberworld? As compared to ordinary ethnomusicological field settings, the virtual laboratory environment offers unparalleled levels of observation and control, allowing us to answer questions about such dependencies in ways unachievable in the real world.

In particular, we are concerned with two primary clusters of independent variables known by ethnomusicologists to shape the emergence of musical community: the social and the musical. Here, social variables include the number and demographic profiles of cyberworld participants, while musical variables include the number and kinds of music tracks populating the map. Variables within either cluster can be manipulated: the former through participant selection, the latter by loading different collections of music tracks into FiW. Participants are selected from among a volunteer adult population, subject to informed consent and the availability of a common language for communication. Researchers perform participant observation from within the cyberworld, embedded as virtual ethnomusicologists and entering into the cyberworld’s virtual intersubjectivity, using multipresence to assume one or multiple avatar identities.

Adopting a more observational, bird’s-eye mode, researchers may also document the total system from without, either in real time or subsequently, by analyzing avatar worldlines along with timestamped transcripts of avatar communications. Currently such transcripts are not archived, but future research regarding such close analysis might motivate such logging. Combining these complementary subjective and objective perspectives with associated qualitative and quantitative analysis offers a powerful new approach to ethnomusicological study, one of increasing relevance as the rate at which we inhabit such virtual spaces in our everyday lives continues to escalate.

Rasika Ranaweera, Michael Frishkopf, and Michael Cohen

Get connected

Running Folkways in Wonderland:

- Click this link to open the server’s Open Wonderland installation

- Then click the “Launch” button to download the file jnlp.

- Make sure you have Java (versions 7 or 8) installed, and that

“http://nelly.u-aizu.ac.jp:8080” is added to your Java Security > Exception List. - Then double-click jnlp to download and run the FiW cyberworld client on your computer. Note that the first time you run Wonderland, it will take a while for the application to download.

- You will be asked to log in. Your username will become your name in the virtual world. No password is required.

Navigating Folkways in Wonderland:

- Click on your avatar, then use the up and down arrow keys (or W and S) to move forward and backward, or page up and down (fn arrow on a Mac) to move up and down (hold down shift to run). Use the left and right arrow keys (or A and D) to step left or right.

- Scroll to zoom in and out, and control-drag to look around.

- Change your view by using the View menu to select a camera type.

- Use the Tools menu to determine whether Collision or Gravity is enabled (if not you can move through solid objects or defy gravity).

- The Help menu provides additional resources, or consult the Useful Links below.

Useful Links

Project site: http://bit.ly/FiWonder

- Quick Start Guide (including Navigation in Open Wonderland)

- Learning the basics of Open Wonderland

- Open Wonderland Home

- Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Publications

Rasika Ranaweera, Michael Cohen, and Michael Frishkopf. Narrowcasting Enabled Immersive Music Browser for Folkways World Music Collection. In Int. Conf. on Computer Animation and Social Agents. May 2013, Istanbul. http://www.cs.bilkent.edu.tr/~casa2013.

Rasika Ranaweera, Michael Frishkopf, and Michael Cohen. Folkways in Wonderland: a Cyberworld Laboratory for Ethnomusicology. In Int. Conf. on Cyberworlds. Oct. 2011, Banff. http://cw2011.cpsc.ucalgary.ca.

Many thanks to folkwaysAlive! at the University of Alberta, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, and the University of Aizu, for their support of this project.

Figure 3. Map Window: Locates currently selected track’s origin in a Google map.

Figure 3. Map Window: Locates currently selected track’s origin in a Google map.

Pingback: Folkways in Wonderland | Bibliolore